could any such superfluities as paint, wall paper, or carpets be found. According to Governor Emory Washburne, of the class of 1817, "the entire furniture of any one room, excepting perhaps the bed," was not worth five dollars in his day; and the institution had then completed its twenty-fourth year. Everything was on a simple and elementary scale. Dr. Robbins, of the class of 1796, whose diary for that year has been printed, made an entry Jan. 26 to the effect that "My father" —a prominent trustee of the college— "and I went to the woods and got a good load of wood." The educational appliances of the institution— curriculum, library, and philosophical apparatus —naturally shared in the general narrowness and limitation. Dr. Robbins was a faithful, studious man; yet little trace of the class-room appears in his diary. He merely speaks of "reciting" Paley's Moral Philosophy and Vattell; of "disputing" once before the president and of a final examination, on the 3d of August, in which the questions "went round ninety times." In the way of recreation, dancing seems to have occupied the place which athletics now hold. Balls were surprisingly frequent. Matters went to such extremes that "the president put an entire stop to a dancing school" on the 30th of April, —a proceeding which seems to have awakened considerable indignation. The only positive intellectual progress, during these first years, was in the direction of geology, a subject for the prosecution of which the situation of the college offers many advantages. In 1809, Prof. Amos Eaton, of the class of 1799, delivered a course of geological lectures, which are supposed to be the earliest ever delivered in an American institution.

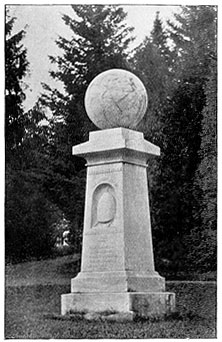

The Mission Monument. But the most important event of this period, whether we consider its effect upon the public or upon the college itself, lay outside the regular educational routine. That event was the "haystack prayer-meeting. For the first thirty years of its existence the moral and religious condition of the college could hardly be considered satisfactory. The president found it necessary on occasion to protest publicly "against drinking parties after examinations." Nor would current views of theology have been acceptable to the Westminster divines. Though its situation might have been expected to raise effectual barriers against such an invasion, French infidelity, nevertheless, reached the college and obtained no little vogue among the students. Occasional revivals of more or less power had sprung up, but at no time could the general atmosphere be considered religious. In the summer of 1806, Samuel J. Mills and a few other students were accustomed to hold prayer-meetings on Saturday afternoons in what is now Mission Park. They went there not so much because they preferred open-air services as because they would be free from molestation, —an immunity which they might not have enjoyed in the college buildings. One hot day they took refuge under a haystack during a violent thunderstorm. Mills's attention had been drawn to Asia, partly by the study of geography, then included in the college course, and partly by events taking place—

-- page 164 --

Previous Page | Next Page

|

These pages are © Laurel O'Donnell, 2005, all rights reserved

Copying these pages without written permission for the purpose of republishing

in print or electronic format is strictly forbidden

This page was last updated on

08 Feb 2005