Williams College.

would attract attention in any assembly. "Take him all in all," wrote a contemporary, himself an eminent divine, "he was the prince of preachers. . . . The learned and the ignorant, the exalted and the debased, the humble believer and the bold infidel, seemed to hang upon his lips with equal interest." And yet he deliberately went out into the wilderness and pitched his tent there. "He conferred with me in 1821," said Dr. Samuel H. Cox, "when about to accept the presidency of Williams College. What so swayed him in its favor? He had offers in other directions. It was religion in general, and the haystack in particular." Without question the Saturday-afternoon prayer-meeting of Samuel J. Mills brought him to Williamstown. Probably no other man could have saved the college, and Dr. Cox was right in saying that if he had declined the task, the whole institution, haystack and all, "would have been serenely anchored amid the sunken reefs of oblivion." The methods by which President Griffin weathered the storm were characteristic. He accomplished his great work not by pedagogical or intellectual instrumentalities, but by the inspiration of revivals, which culminated in the great awakening of 1825, when nearly every undergraduate was converted. The power of his presence and words was often overwhelming. A student of his relates an incident in this revival which illustrates it. The work went on until the whole college had been reached, with the exception of eighteen men. Word was brought to him one morning to this effect. In the evening there was a meeting, at which, in spite of storm, darkness, and mud, every student is said to have been present. "We waited in breathless silence for the Doctor. He came, and the lecture-room was so crowded that he stood in the door, whilst giving his hat to one, and his cloak and lantern to others. He stood a moment gazing through his tears on the crowd before him. Then clasping his hands and lifting up his face to heaven, he uttered in the most moving accents these words: 'Or those eighteen upon whom the tower in Siloam fell, think ye that they were sinners above all men that dwelt in Jerusalem?' The effect was overpowering. For minutes he could not utter another word, and the room was filled with weeping." Both President Griffin and his successor said that this revival saved the college. The situation just before it began was desperate, —trustees ready to give up the struggle, students disheartened, and the faculty on the point of breaking up. But the revival created a new life in the institution and among its officers, and awakened public interest in its fortunes, while it wrought up the president to feel "that if ever a man was bound to go till he fell down in the service of an institution . . . he was that man." And he did go until the funds were raised which made the future of the college secure.

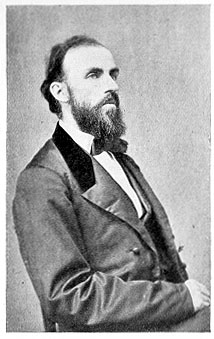

Prof. A. L. Perry, 1863. Dr. Griffin's genius lay in the line of revivalism. He does not appear to have been especially interested in the ordinary work of the class-room, unless an exception should be made in regard to rhetorical criticism, which seems to have been rather agreeable to him. In the performance of it he cut and slashed a good

-- page 168 --

Previous Page | Next Page

|

These pages are © Laurel O'Donnell, 2005, all rights reserved

Copying these pages without written permission for the purpose of republishing

in print or electronic format is strictly forbidden

This page was last updated on

08 Feb 2005