But Dr. Hopkins's real work was done in another sphere. At the outset he saw clearly the necessity of reorganizing the curriculum so that the various studies, which heretofore had been pursued in a random fashion, should be reduced so far as possible to a system, in order that they might have some unity of effect on the student's mind.

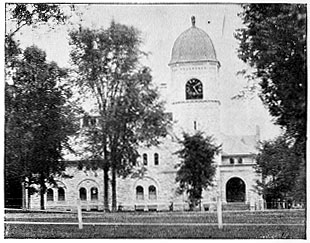

Lasell Gymnasium.

No doubt a physical factor of considerable importance entered into Dr. Hopkins's remarkable successes. He had a noble presence. There came to be something kingly in his bearing and aspect as the years went on, and the young men were not insensible to their charm and power. Then Dr. Hopkins knew human nature, and was able to individualize in his instruction. He somewhere says that students cannot be taught properly in the bulk. The instructor must understand the temperaments, appetencies, moods, and approachable points of the youth he is trying to educate in order to do his work well. What is more, his insight must also extend to the relations and adaptations of truth; must detect what phases of it are likely to attract and to stimulate. In this work Dr. Hopkins had ability of the highest order. He could invest the profounder questions of philosophy, ethics, and theology with a fascinating interest. From the time of their entrance into college, students eagerly looked forward to the luminous and inspiring days of senior year. The method which he pursued was for the most part that of discussion. He seldom gave formal lectures. The students were expected to acquire a general knowledge of the subject in hand from text-books, and the hour in the class-room was given up to a conference upon it. Practically the exercise amounted to what we now call a seminary, the conduct of which, in methods of interrogation, in clearness and vigor of exposition, in exhibiting the strength or weakness of any position that may have been taken, in dealing with queries, conjectures, and objections, fairly entitle it to be ranked among the fine arts.

-- page 171 --

Previous Page | Next Page

|

These pages are © Laurel O'Donnell, 2005, all rights reserved

Copying these pages without written permission for the purpose of republishing

in print or electronic format is strictly forbidden

This page was last updated on

08 Feb 2005